"A rising tide lifts all boats." This quote, famously attributed to President John F. Kennedy, speaks to an effect where a flood of economic activity will bring prosperity to all. The problem today, however, is that not everyone is in a boat.

We live in a world of opposite problems. Problems that, in one example, have converged in the form of affordable housing and the urban/rural divide. The opportunity is in front of us to solve these challenges, and the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown has illuminated the path forward. The virtual workforce is here to stay, and it is just what small towns need for economic recovery. At the same time it offers a pressure release valve for urban areas being crushed by the rapid cost escalation of housing.

The fortunes of booming economies in places like Seattle, where I live, have created a situation where a flood of demand from high earners has resulted in an overheated housing market. At one point, 37.8% of Seattle home sales involved a bidding war, according to Redfin. Small towns also have an affordable housing challenge, but in their case insufficient economic activity has created a glut of cheap housing that few can afford.

A Tale of Two Cities

There is a reason why these two affordable housing conundrums mirror each other. No one disputes the negative impact of concentrated poverty, and great efforts have been made to address this as an issue. But few realize that concentrated prosperity is equally detrimental to community health. Our communities are typically segmented into camps and often pitted against one another. It is uncomfortable to consider that concentrated prosperity and concentrated poverty are two sides of the same coin. This, however, reflects reality whether we are comfortable with it or not. Leaning into this discomfort might be what it takes to solve these interconnected challenges in a way that benefits all.

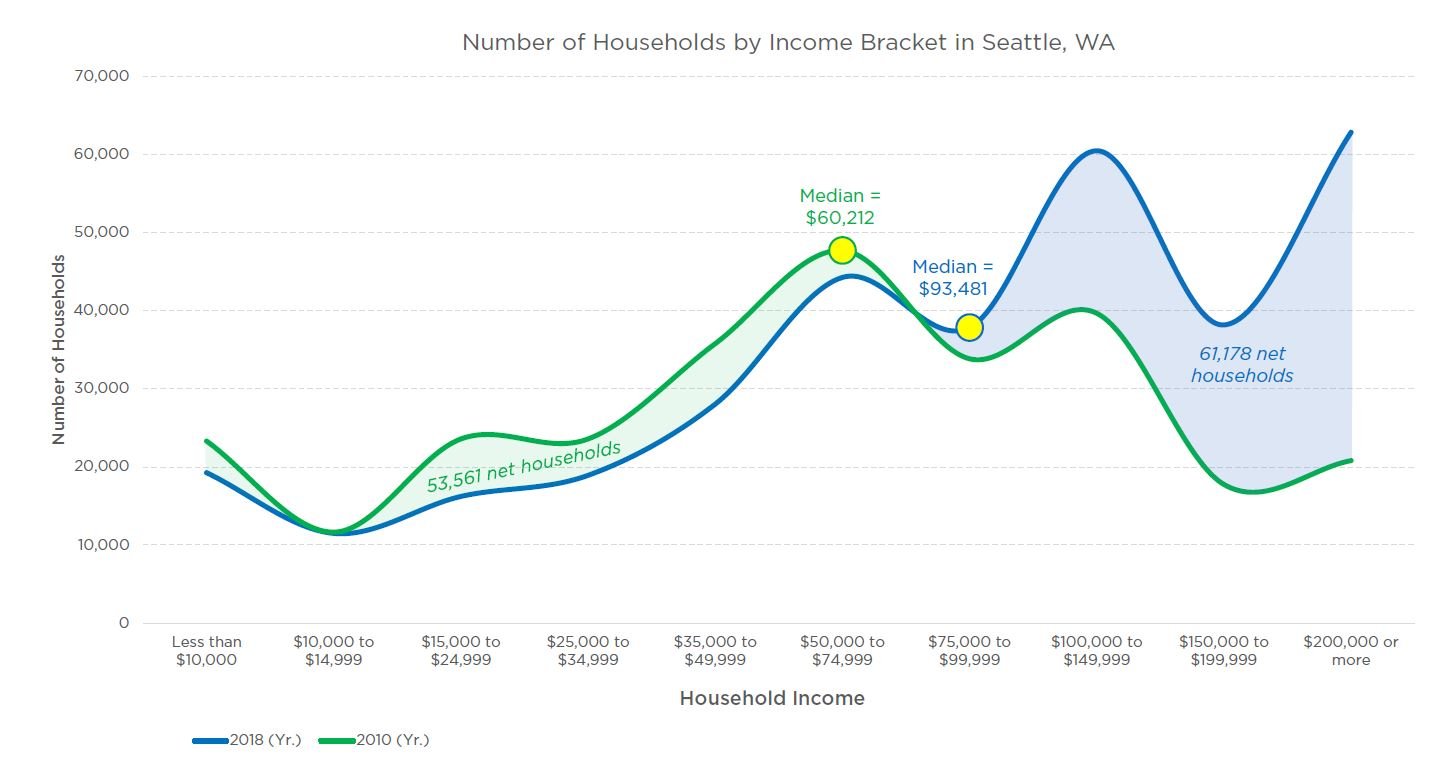

In Seattle, median household income increased by over $33,000 in eight years. This is an astounding amount, and it is driven by an explosion of high wage earners. While the amount of lower income households has slightly decreased, the general distribution has remained relatively stable. Meanwhile, median home sale values increased by 83% from April 2010 to April 2020 totaling $762,000, according to Zillow data. To afford a median price home, a household would have to make about $154,000 annually. The data is clear: urban home ownership is out of reach for all but the highest wage earners.

Data can tell or minimize an underlying story: B+H analyzed U.S. Census data that reports the distribution of household income as a percent of total households. Growth disparity is more drastic when considering the volume change of households by income rather than the distribution of income by total households.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2006-2010 and 2014-2018

In small towns across America, the economic story has been very different. It is more akin to Greek mythology’s Sisyphus; the character destined to eternally push a boulder up a hill, only for it to fall once it nears the top. This is a tragedy that many in small town America can relate to. Here’s a sobering picture:

- The U.S. has lost 75 million farms since its peak in 1935.

- 5 million manufacturing jobs have been lost since 1980.

- The median income from family farm production is negative.

- 41% of principal farm operators have another job as their main source of income.

- Manufacturing production has increased by 69.6% yet wage growth increased by 11.6% since 1979 after adjusting for inflation, as analyzed by the Economic Policy Institute.

Between forces such as agricultural consolidation, urban sprawl encroachment on rural lands, and threats to blue collar employment from globalization and automation, the lifeblood of small town America has been slipping away for decades.

Among the best available strategies, and one that most of America’s small town economic development has relied on, has been to do whatever it takes to bring back manufacturing, food processing or warehousing jobs. Even when this has been successful, it has been inadequate. Fewer jobs come back, and wages are often lower than previous levels. Economic stagnation should not have to be the best-case scenario for any community.

The Illusion of Choice

With these prospects, it is no wonder that more people live in urban areas than ever before. This influx to cities has created an imbalance, and urban living is not necessarily the preferred choice. There are many people who live in cities who would prefer a more rural lifestyle, but their job doesn’t allow it. 19% of the U.S. population lives in a rural area, but a Gallup poll shows that 27% would prefer it. A small town can be extremely attractive to those who would like more space for their family, a beautiful home they can afford, to be closer to nature, and immersed in a culture that prioritizes the simple pleasures of life over the fast pace of a city. Conversely, there are many people who prefer the city lifestyle, but the intimidating cost of living puts it beyond their reach. In both cases, economics is driving a behavior that is misaligned with personal preferences. As the saying goes, “Freedom isn’t free.”

The time to change this is now. The COVID-19 pandemic has pierced the misconception that white collar work needs to occur in an office in a city. The world has realized that this work can happen anywhere. It’s been true for quite some time, but only now has our forced experiment proven at scale that operations can run smoothly without people being in the office.

The workforce wants change too. Gallup published a poll showing that 62% of workers are remote as of the beginning of April 2020. Among those who are working remotely, 59% stated that they would like to continue to do so as much as possible after the crisis subsides. It is an astounding change in perspective, and it offers a long overdue opportunity for the revival of a coveted American way of life.

Investing in What We Hold Dear

The most exciting part of this prospect is that it wouldn’t necessarily require a huge flood of people to make a big impact, but rather a modest rebalancing. Take a town like Albert Lea, Minnesota, located about 90 minutes south of Minneapolis. It is a bit too far for a daily commute to the city, but it could be a convenient location for people who only need to pop into the office once a month or once a quarter.

It is a beautiful place. My grandma lived there for a time, and I still have family in the area. The town is nestled between two of Minnesota’s 10,000 lakes, giving inspiration to its slogan, “The Land Between the Lakes.” It is a small city of 17,647 people (2018 est.). It experienced a boom from the 1870s to the 1970s following the expansion of the railroads and subsequently agricultural businesses, and in particular - meat packing. In fact, Cargill Corporation, an agricultural giant and the world’s largest privately held company, was founded in Albert Lea in 1870 to take advantage of the railroad. Cargill currently operates a meat packing operation there.

This 100-year era of investment from 1870 to 1970 is visible in the town’s architecture. The center of town has a beautiful collection of stone and brick commercial buildings that speak to the artistic detail and hand craftsmanship of a town showing off for visitors along the rail line. The housing stock, too, is full of historic character. Homes with porches, yards, large rooms with wood floors, fireplaces and stained-glass windows are easy enough to find. They are relatively affordable, too. The median value of owner-occupied housing is $97,700 (U.S. Census, 2018), which is just under half the U.S. median.

Since its peak population in 1970, the town has seen a decline of 9.1%. The story has largely been one of gradual employment loss over time, often through closing of plants after consolidation, acquisition or accident (in 2001, the largest meat packing operation that employed 500 people closed following a fire). The town has been somewhat successful in replacing some of the losses through investments from employers such as the Mayo Clinic and Walmart, but those successes have not been enough to generate population growth.

To get back to its peak population by the 2030 Census, Albert Lea only needs to grow by about 150 people every year, that’s about four to six households a month. It is a figure that seems feasible by tapping into a remote workforce. If investments like this occurred, there would undoubtedly be other positive cascading effects to local businesses and to public funds. In other words, a big win for the community.

A Future for People

There are a lot of towns like Albert Lea. Adopting a new strategy that aims to attract people, not just large businesses, could offer the opportunity for creative new approaches to economic development. These strategies might include investments in local schools, high speed technology networks, art, environmentally sustainable infrastructure, grants for local business start-ups, and promotion of local food systems. Ultimately, any one of these initiates would not only be a draw for new residents, but would underpin a more diverse and self-sustaining economy over the long-term.

We have the opportunity to generate positive outcomes from this global pandemic. My hope is that we use this period to begin to heal old wounds and cultural divides that have haunted society for generations. It is not only an opportunity, but our obligation to one another.

President Kennedy described this ideal in another famous quote, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” We have the ability to help ourselves by helping each other. If we choose it, COVID-19 might just provide the lifeboat we all need.